African countries are planning to launch their own financing vehicle for oil and gas projects in the face of growing pressure from Western financial institutions to abandon the development of these resources. The group of 18 states needs $5 billion to kickstart what it calls an energy bank.

They call themselves the African Petroleum Producers Organization, according to a recent report in the Financial Times that said African resource-rich countries have grown frustrated with Western banks’ refusal to lend money for the development of oil and gas fields, to which they believe they have a sovereign right. It’s hard to argue with that.

“[These] are countries at a development stage where you cannot suddenly move into green [transition] . . . you cannot just say funding is cut and they can’t do oil,” Haytham El Maayergi, global trade executive VP at African Export-Import Bank told the publication in an interview. Afrexim Bank is partnering with the 18 states to set up the new institution.

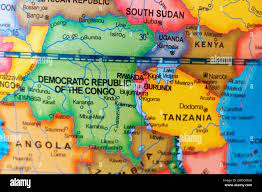

Africa is the continent with the smallest carbon footprint. It’s also a continent rich in yet-to-be-tapped oil and gas. Under pressure from pro-transition Western governments, international lending institutions such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank have stopped providing money for such energy projects, limiting these countries’ chances of taking advantage of their own resources the way countries such as the United States are doing.

The U.S. is the second-largest shareholder in the African Development Bank, per the Financial Times. Not only that, but Biden administration officials have recently praised the latest boom in U.S. shale oil and gas at the same time as that government’s representatives in the ADB favor no oil and gas development in Africa. That must sting.

“Africa’s context is totally different from what you find elsewhere,” Afrexim Bank’s El Maayergi told the FT, noting that unlike some legacy oil and gas producing regions, much of Africa’s hydrocarbon wealth has yet to be developed, serving t alleviate rampant poverty in many parts of the continent where 600 million have no access to electricity and as many as 1 billion cook with charcoal, dung, and firewood.

Once again, it would be difficult for institutions such as the World Bank—or indeed, private banks—to argue with the assertion that African nations have the right to reap the same benefits from hydrocarbons that Western nations have reaped for decades before they decided to shift beyond oil and gas. It would be especially difficult because that shift is proving trickier than its architects expected and the Western world remains essentially as dependent on oil and gas as before.

Meanwhile, African governments are dealing with boycotts by banks and, most recently, insurers, themselves the object of growing pressure by climate activists, who insist that Africa must remain the least emitting continent, leapfrogging the hydrocarbon era and moving straight from charcoal to wind and solar. International lenders such as the WB and the ADB would be only too happy to finance such projects. Yet there is a problem with those.

Solar and wind farms generate electricity by capturing the light of the sun or the energy of the wind and converting it into electricity. This electricity then needs to be transmitted to where it will be used or stored. It is at this point that one of the challenges specific to Africa rears its head: transmission.

Many African countries simply lack transmission infrastructure extensive enough to accommodate utility-scale solar and wind installations economically. After all, a company cannot just build a solar farm at a random spot only because it is near the existing infrastructure. Solar and wind farms require optimal conditions to perform well. The fact that transmission is a problem even in mature wind and solar markets such as Europe speaks volumes about the size of the challenge of the transition in African countries.

So, African states are getting together to find an alternative to Western lenders. For now, the 18 members of the African Energy Bank initiative have agreed to each contribute $83 million towards the bank, for a total of $1.5 billion. Afrexim Bank will match this amount, leaving a gap of $2 billion that needs to be filled by external institutions such as sovereign wealth funds, private funds, and other banks, the FT report said.

According to the African Energy Chamber, a group advocating for the development of local oil and gas resources, there are 125 billion barrels of oil and 620 trillion cu ft of natural gas waiting to be tapped. Luckily for those eager to develop their own resources, Big Oil, if not Big Bank, is rather interested. And it is already moving to explore these resources despite the relentless pressure from activists. Namibia is a case in point, as the country eyes the rank of fifth-largest oil producer in Africa by 2035, but so are countries such as Uganda and Senegal, in addition to legacy producers such as Nigeria, Angola, and Libya—all but Uganda members of the African Petroleum Producers Organization.

Iran Energy News Oil, Gas, Petrochemical and Energy Field Specialized Channel

Iran Energy News Oil, Gas, Petrochemical and Energy Field Specialized Channel