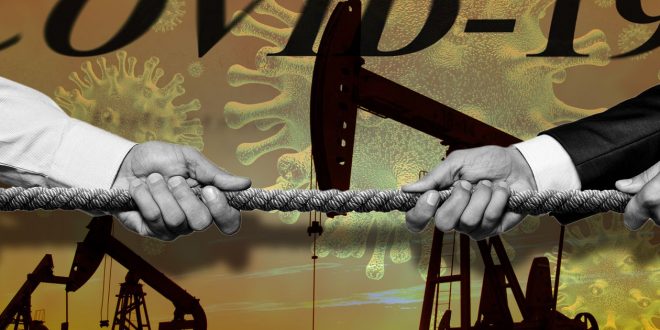

OPEC’s oil ministers have a few challenges to consider at a crucial summit next week, but for the first time in years, the U.S. shale boom won’t be at the top of the list.

The global coronavirus pandemic continues to play havoc with the world’s economic sector, and oil prices have suffered. And after years of unparalleled growth, the nation’s shale industry – responsible for making the U.S. the world’s biggest oil producer – is now realizing there is no light at the end of the tunnel.

According to World Oil, while the growth of shale was made at the expense of crude oil-producing companies in the Middle East and Russia, with all that has transpired in the past year, “it’s now abundantly clear who has the upper hand in the global oil market.”

“In the future, certainly we believe OPEC will be the swing producer — really, totally in control of oil prices,” Bill Thomas, chief executive officer of EOG Resources Inc., the biggest independent shale producer by market value, said earlier this month. “We don’t want to put OPEC in a situation where they feel threatened like we’re taking market share while they’re propping up oil prices.”

Right now, an impromptu virtual meeting scheduled for Sunday between OPEC+ members is taking center stage, with members seriously considering production cuts for another two to three months into 2021. It’s not clear if all the member countries will have to abide by production cuts, but Libya, Nigeria, and UAE are among the countries pushing back against the cuts.

OPEC+ members are worried, and the tensions are high. The oil market this past week fell from an eight-month high, with futures falling 1.6 percent in New York. On Friday, Standard Chartered’s Paul Horsnell said, “The post-vaccine announcements and post-U.S. election oil price rally is a mixed blessing for Saudi Arabia and its main ally in oil policy, Kuwait, The rally has increased special pleading from the more reluctant members of OPEC+.”

Iraq is one of those more reluctant members. Iraq’s deputy leader was critical of OPEC, saying the economic and political conditions of member countries should be considered before they are asked to withhold production.

The U.S. shale industry

The start of the pandemic, along with the Saudi-Russian price war created a collapse in oil prices in March. U.S. drillers immediately scaled back capital spending and cut production by more than 2 million barrels per day between April and June. Be that as it may, investments dropped and thousands of jobs have been lost, with many of them never coming back. Even worse, many companies have resorted to taking bankruptcy.

Federal relief – especially royalty rate reductions on federal land and offshore, has not been very effective because of a lack of uniform decision-making, the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office (GAO) said last month. Environmental activists have also jumped into the fray, wanting to know why the government “dared to provide relief for the fossil fuel sector,” reports Oil Price.

However, jobs were saved by the feds stepping in during the pandemic. From July, the Paycheck Protection Program, with more than $1 billion in forgivable loans to companies, helped to save more than half of oilfield jobs in Texas. This amounted to saving 93,117 jobs or more than half of the 182,500 people employed in the sector in Texas.

Even though problems caused by the pandemic and continuing cuts in oil production are present-day worries, the U.S. shale industry has an added worry, now that the election is over. While President Donald Trump was a force in igniting the shale boom that made the country a leader in oil production, President-elect Joe Biden has vowed to ban new oil and gas drilling on federal lands and waters.

Iran Energy News Oil, Gas, Petrochemical and Energy Field Specialized Channel

Iran Energy News Oil, Gas, Petrochemical and Energy Field Specialized Channel